Duplicate content can sometimes exist in a website, especially for larger sites such as ecommerce sites that offers a lot of products in different variations. This is also the case for blog sites and some blog posts that gets re-published in other websites by the author. Duplicate content, while not a penalty, still poses some issues, especially when it comes to search and ranking in Google and other search engines. This is where canonical urls and the use of canonical tags comes in.

In this article, we will talk about canonical urls, what they are, the importance of setting canonical tags, and how to set a canonical link element. I also provide 3 factors to consider when setting URL canonicalization for SEO benefit.

While I say ‘3 factors,’ there might be more than what we’ve outlined below. This depends on a few things, such as how many pages or piece of content your site has, how many of your pages can be deemed as duplicate pages, how tracking IDs are added onto your URLs, and a host of other factors.

With that in mind, Google has a page that dives into a bit more extensive detail: https://developers.google.com/search/docs/advanced/crawling/consolidate-duplicate-urls

You probably know this, but haven’t given it much thought.

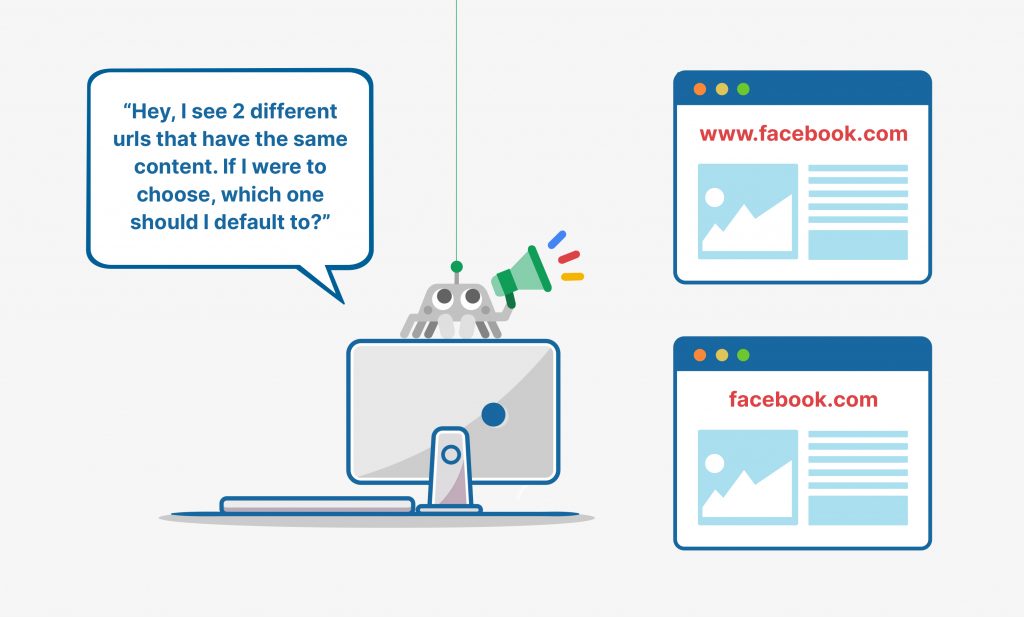

You want to go to a certain website–let’s say, Google or Facebook.

You type in google.com or facebook.com

Good.

You also know that if you type in www.google.com or www.facebook.com (emphasis on the www. portion) you go to the same sites.

So, for most top-level domains, whether or not you type in the www. portion of the address, you’re taken to where you want to go. (This doesn’t quite work with addresses that have non-www subdomains in them, but we’re digressing.)

As far as most visitors are concerned, there’s no difference between google.com and www.google.com (Technically, there is, and people are sometimes directed to the www version, but that’s outside our scope.)

So, as far as we’re concerned, there’s no difference.

But, for the search engines and their search crawlers, there can be.

That brings us to the years-old discussion of duplicate content.

Let’s clear up a misconception: there’s no duplicate content penalty per se; rather, it’s more of a filter.

Let’s first define duplicate content: it’s roughly where two or more differentiated pages (urls) have enough identical content that they’re practically the same. It’s almost like having an original copy of a document and having a photocopy of that document.

If you consider a large e-commerce site with many, many products, there’s a possibility that 2 or more pages have duplicate content.

For example, consider 2 widgets that are 99% identical, the only difference being their color.

If each of these widgets had a separate page, there would effectively be 2 pages that share 99% identical (duplicate) content.

(In fact, we don’t even have to use the example of 2 separate pages: there can be different url variations of a single page, and that can lead to duplicate content.)

Google knows this, so they don’t penalize sites for this. Instead, it’s more of a filtration process that takes place: they try to offer the page that they think is best for the user. (In this case, perhaps a differentiating factor may be the page that gets more traffic, or the more popular of the two widgets.) Then, the duplicate versions are filtered out from the results.

Anyway, you’re probably wondering, “If duplicate content issues doesn’t cause a penalty, what makes it so bad? Why the debate?”

Well, duplicate content isn’t a huge issue, but ideally, it’s something to be avoided.

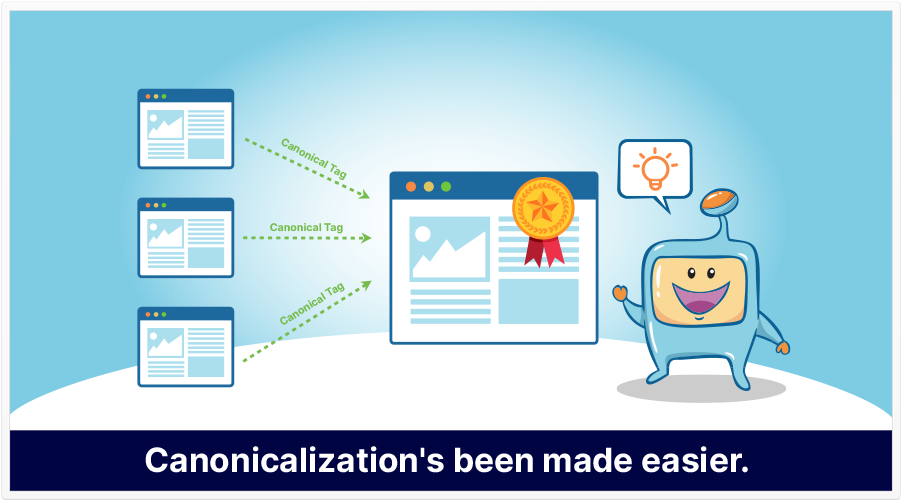

URL Canonicalization or adding a canonical tag to your urls is a tag that tells search engines that the canonicalized url is the original version of the page and the non-canonical pages are duplicate versions of the original page.

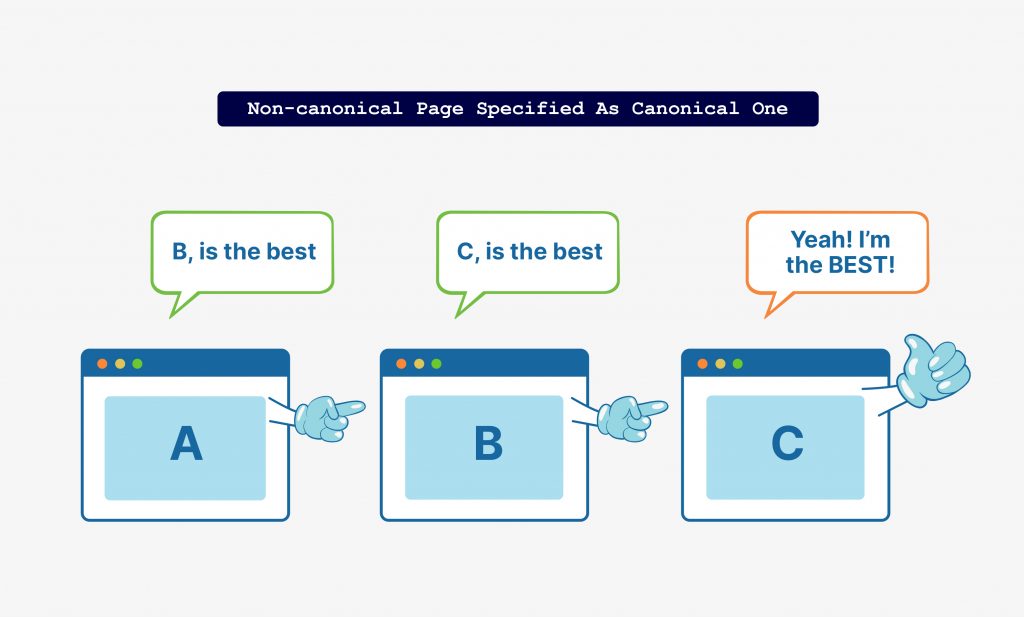

Adding the canonical tag rel=”canonical” prevents issues caused by duplicate content that show up in different pages of a site. As I mentioned earlier, while there is no penalty for duplicate, the same content that shows up in multiple pages trigger a filter that filters out some duplicate content. It is up to the search algorithm to choose which particular page among the pages with duplicate content it will rank in the search results.

Using a canonical tag tells the search engines that this is the original piece and this is what should appear in search results. This way, ranking pages that you would not want to be ranked will not happen and what will be ranked will be the original source that you would like to be ranked. The right page will also get the organic traffic from the search query.

We opened this article by talking about www. and non-www. versions of websites (ie, www.facebook.com and facebook.com).

When Googlebot (or most search bots) sees a page that has www. and non-www. variations, it hypothetically asks, “Hey, I see 2 different urls that have the same content. If I were to choose, which one should I default to?”

Now, this isn’t a dilemma for Google: where appropriate, it’ll make a decision and choose one of the urls, even if you don’t determine one by using a canonical tag.

But there’s something else to consider.

If you’re at all interested in the SEO benefit of having unique (non-duplicate) content and the ‘link juice’ that comes to your site, there might be a bigger reason why you should consider canonicalization.

Link juice is a term we use in the SEO industry. Without getting into too much detail, it’s actually an echo of something Google used to publicly display: Page Rank. (Page Rank is no longer publicly available, though it may be used internally at Google.)

Anyway, the gist of what I’m trying to say is that most web pages that are indexed by Google have some sort of merit or ‘voting’ power.

One factor that Google uses to rank a web page (and site) has to do with the links pointing to that page. Any time a web page links to another web page (whether it be from within a site or from one site to another), it counts as a ‘vote’ in favor of the page that’s being linked to.

So, when one web page links to, or ‘vote’ for another web page, some ‘link juice’ flows from that web page to the page that it’s linking to (generally speaking).

What I’m about to say is a bit of an oversimplification, but it illustrates my point: the more sites that link to yours, the better.

“Alright,” you say. “So, what does that have to do with canonicalization?”

So, let’s say that there are 2 sites that link to your home page. One site uses a non-www. url (such as yoursite.com) and another site uses a www. url (such as www.yoursite.com).

Link juice flows from each of these 2 sites to 2 different versions of your site.

Think about it: this link equity is being diluted by 50%.

Wouldn’t it be better if the link juice was consolidated, and went to one preferred version of your site, so that instead of getting the benefit of only 1 site linking to you, you get the benefit of both sites that are linking to you?

Now, in all transparency, we don’t know exactly how the Google algorithm works, and what I just explained is a bit of an oversimplification, but we have reason to believe that this is a sound way of thinking.

That’s why canonicalization can be beneficial for SEO. It helps you to consolidate your URLs and get maximum ‘link juice’ benefit from the links going to your site. Setting a proper canonical url to duplicate versions of your site tells search engine that these non-canonical version are duplicate versions and they can then count all the link signals pointing to the other versions as links to the canonical version. This is the SEO benefit you can get from setting your canonical pages – strengthening your link building with consolidated metrics and and making sure that links are appropriated to the right page.

Before we get into the 3 factors, we want to advise you that, depending on the complexity of your site, you may have to take into considering more than these 3 factors when you implement canonicalization. That said, we feel that the following are 3 factors that every webmaster will have to consider.

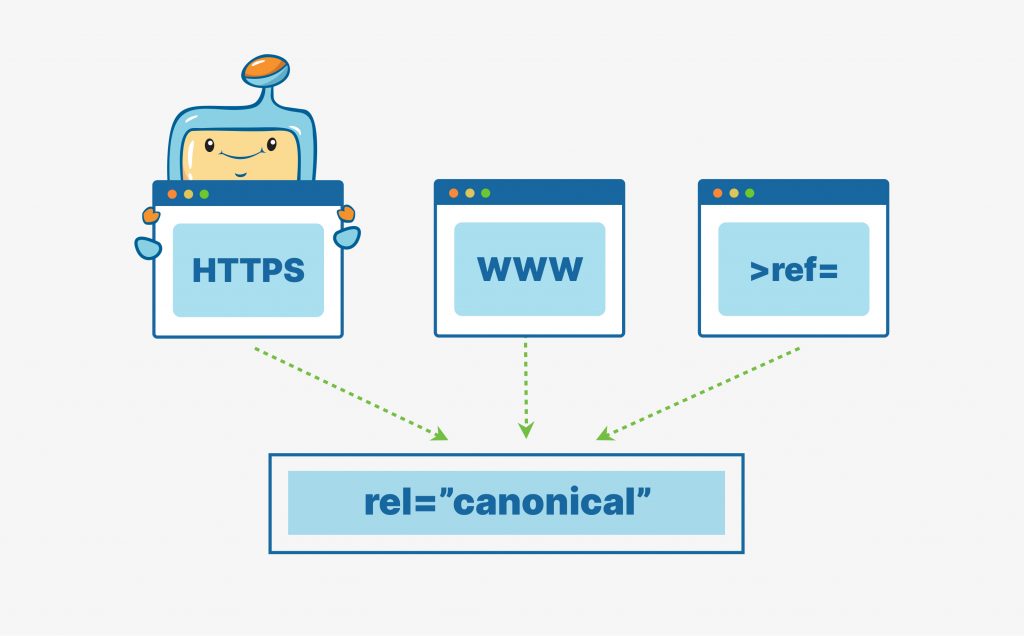

Decide if you’ll have an HTTPS site or simply an HTTP site. We advise you to go with Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS), which implies SSL (Secure Sockets Layer). SSL means that data shared between the end-user and the site is encrypted (secure).

Most good modern web hosts offer free SSL, and if your host doesn’t, there may be other ways you can implement SSL on your site. If you’re using WordPress, there may be a plugin that can freely do this for you. One such plugin to consider might be WP Encryption – One Click SSL & Force HTTPS.

When it comes to moving from HTTP to HTTPS, another option to consider is setting a 301 redirect status codes from your HTTP pages to your HTTPS pages. This would be an easier solution and would help lessen the possibility of duplicate content.

Yes, each page has a different url parameter, and therefore, canonicalization is done on a page-by-page basis, but depending on the solutions you have available to you, you can have canonicalization automatically implemented on each page of your site.

This is ideal if your site has a very manageable url structure and you don’t have several product pages that essentially feature the same product. (If you’re using WordPress, a good SEO plugin may have this feature. An example of a plugin that has this is Yoast SEO)

If your site is new and uncomplicated, this step may not apply to you, but it’s still one to consider for the future.

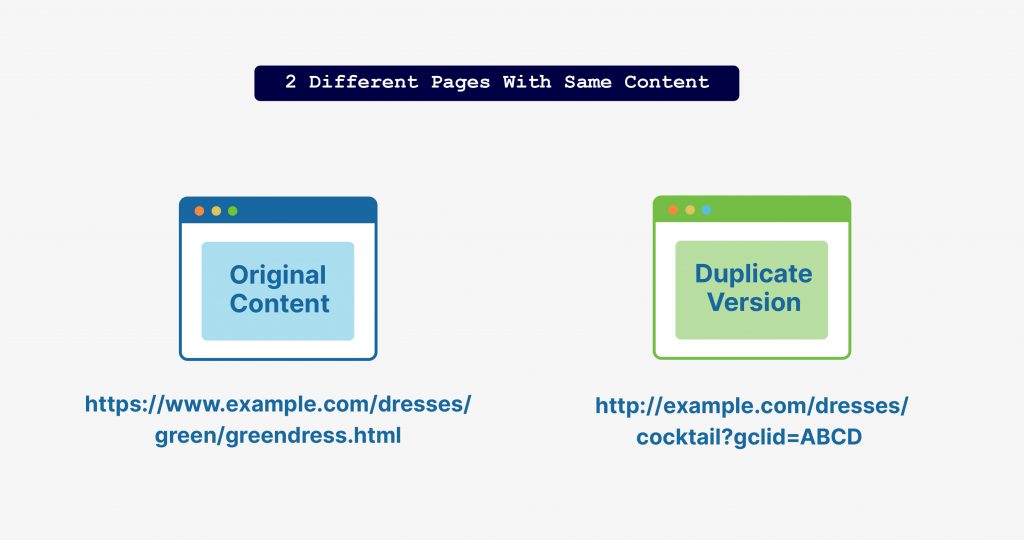

For example, look at this url:

http://example.com/dresses/cocktail?gclid=ABCD

Now, look at this one:

They both look vastly different, because:

However, would you believe that, despite how different these 2 are, they both have the same content?

Yes, although these urls are purely hypothetical, they’re examples of what can, in theory, be two seemingly-different web pages that are actually the same. We actually pulled this example from Google’s web page on consolidating URLs.

If your website has a certain level of complexity, or it’s URL structure is like what we illustrated above, you may have to take extra steps to ensure that each of these pages are individually canonicalized.

We’re going to show you how to add canonical tags to a web page’s code. Don’t worry, if you use a content management system like WordPress, Wix, Shopify, or any of the modern site-building platforms, this should be fairly simple. There are also WordPress plugins that allow you to set canonical pages. What we want you to keep in mind is that canonicalization (at least the way we’re going to show you) is done on a page-by-page basis.)

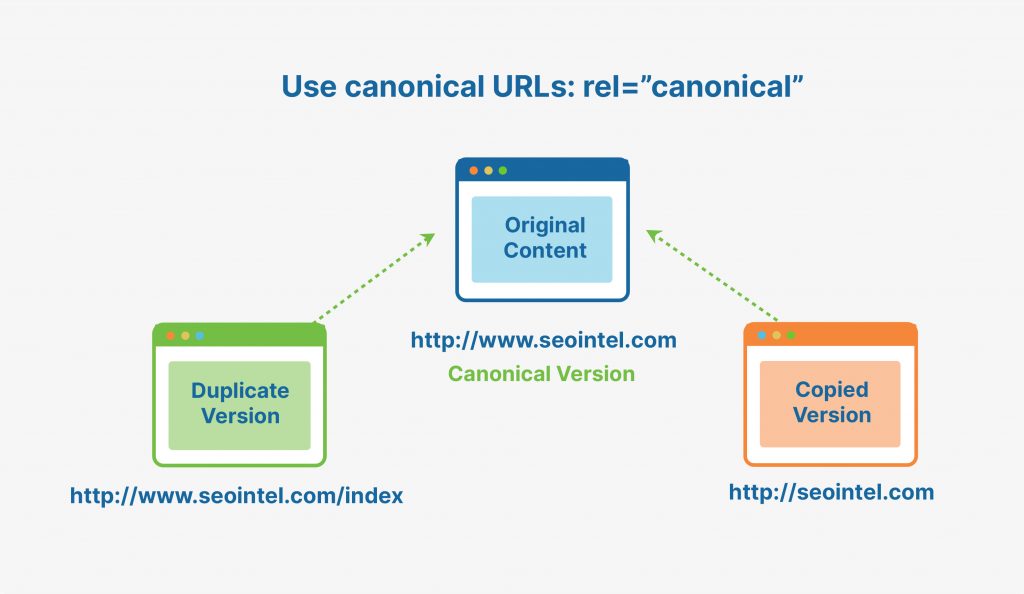

We’ve already established that the same content can appear on two different URLs (ie: a www. version and a non-www. version), and told you of the SEO benefit of consolidating these 2 and declaring one version as the default one (the correct canonical URL).

So, how do you do that?

You do that by establishing that a certain url (version of a web page) is the canonical url. A canonical url is established via a line of html code called rel=”canonical”.

Codewise, this is what it looks like:

<link rel=”canonical” href=”https://seointel.com/” />

This line of code is put in the http header section of the page’s source code, between the opening and closing head tags. (There are head tags, and then there are header tags. Here, we mean the head tags.)

If you look at that line of code, it basically says that the non-www version of this page is the canonical version–or, in other words, the default version. So, supposing that there’s a link going to https://www.seointel.com (the www version), the canonical version is the one that’ll be referenced. It merges the two pages into one, from the perspective of search engines. The code is a soft redirect without actually redirecting the user to another page.

Once this is done, it is a signal for search engines to know which page is the original version that they will be ranking in search, and which page will get all the link juice.

Self-referencing canonical URL is basically setting a canonical tag from the original page to itself. This helps state that the original page is indeed the original version.

If you are syndicating your content for publication and having it published in different websites, it is best to use a self-referential canonical tag on your original article also and to have the syndicated page specify cross-domain canonical urls – that is, establishing that their version is a canonical version and yours is the original. While setting a self-referencing canonical tag does not always prevent the syndicated version from showing in the search results, it helps lessen the risk of the syndicated versions outranking the original content.

We hope we’ve shown you the SEO benefits of setting canonical URLs to your site and individual pages. Canonicalization helps resolve duplicate content issues, consolidate multiple urls for products to a single product to show up in a search query, for your content to be tagged as the original version, for search engines to know which particular page to rank, and to get the maximum ‘link juice’ from the sites that link to yours. We hope that with this guide, you are able to apply the canonical tags and canonical url field correctly, and get that ranking boost to the correct pages of your site.